The U.S.A. may have originated jazz, but jazz has usually received its most intense appreciation beyond the U.S. borders. Unfortunately, except for small enclaves of fans gathered in various jazz societies or in occasional weekend festivals and except for a handful of dedicated LP producers, the American public generally regards classic jazz as a type of pop music that had its heyday some 60 years ago and then, like other ephemera of pop culture, disappeared into a more-or-less deserved oblivion. By contrast, European musicians and critics recognized ragtime and jazz at the outset as a unique contribution to the arts-to this day America’s only native art form, in fact-worthy of being studied, mastered and preserved, communicating the genius of its practitioners in a way that time cannot diminish.

Moreover, overseas jazz observers over the years have tended to see a bigger picture than the Yanks. With few exceptions, latter-day stateside Dixielanders have usually grouped themselves into the conventional six-or-seven-man combos most typical of 1920s units. European jazz men did so too, but they also took time to maintain the sounds that filled the byways of jazz in the twenties. For example, Europe has for some years been well ahead of the U.S. in fielding skilled teams executing the ten-man “hot dance” style that paved the way for the swing era. (For a splendid example thereof, see Stomp Off S.O.S. 1008 by France’s Charquet & Co).

Moreover, overseas jazz observers over the years have tended to see a bigger picture than the Yanks. With few exceptions, latter-day stateside Dixielanders have usually grouped themselves into the conventional six-or-seven-man combos most typical of 1920s units. European jazz men did so too, but they also took time to maintain the sounds that filled the byways of jazz in the twenties. For example, Europe has for some years been well ahead of the U.S. in fielding skilled teams executing the ten-man “hot dance” style that paved the way for the swing era. (For a splendid example thereof, see Stomp Off S.O.S. 1008 by France’s Charquet & Co).

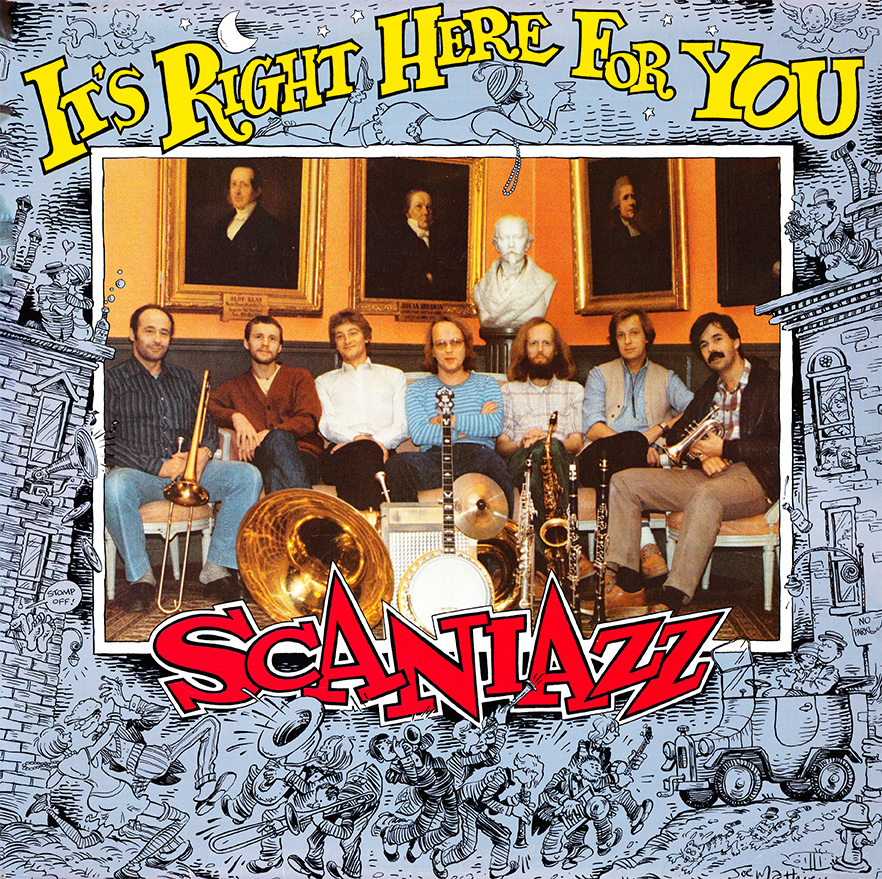

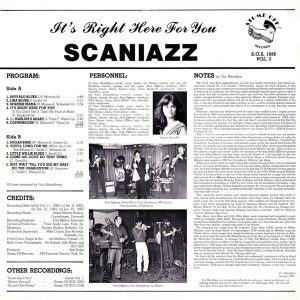

Thus, it comes as no surprise that one has to sojourn to Sweden to hear, live, yet another byway of jazz-the unique acoustical blend that characterizes a vintage platter cut under the leadership of New Orleans pianist / composer / publisher Clarence Williams. Cornetist Paul Strandberg, head man of Scaniazz, demonstrates again on this, the bands third Stomp Off release, the delicate tone and spare phrasing evocative of Ed Allen, who frequently handled Williams’ lead choruses, plus the arranging skill that made Williams’ lineups- often just four or five players- sound much larger. Listen for example to the way Stefan Kärfve’s sonorous tuba and Björn Ekman’s stop-time banjo create the illusion of a full ensemble on the first chorus of You’ll Long For Me (When The Cold Wind Blow), a 1925 Chris Smith- Clarence Williams opus waxed in 1927 for Colombia by Williams’ Jazz Kings.

Thus, it comes as no surprise that one has to sojourn to Sweden to hear, live, yet another byway of jazz-the unique acoustical blend that characterizes a vintage platter cut under the leadership of New Orleans pianist / composer / publisher Clarence Williams. Cornetist Paul Strandberg, head man of Scaniazz, demonstrates again on this, the bands third Stomp Off release, the delicate tone and spare phrasing evocative of Ed Allen, who frequently handled Williams’ lead choruses, plus the arranging skill that made Williams’ lineups- often just four or five players- sound much larger. Listen for example to the way Stefan Kärfve’s sonorous tuba and Björn Ekman’s stop-time banjo create the illusion of a full ensemble on the first chorus of You’ll Long For Me (When The Cold Wind Blow), a 1925 Chris Smith- Clarence Williams opus waxed in 1927 for Colombia by Williams’ Jazz Kings.

While we’re on the charts, it’s worth noting that constant change of tone color is a standard part of a Scaniazz performance. They use a four-horn three-rhythm configuration for most cuts, but keep bringing different musicians to the fore (dig Ulf Björkbom’s flowing soprano sax dancing above the crew on the verse to the 1924 Jo Trent-Fats Waller song In Harlem’s Araby) or bringing them in or out of the group sound (except for a raspy solo and the gliding finale, Arne Højberg’s brawny, back-alley trombone is heard only sparingly, shoring up a few licks on Spanish Mama by Elmer Schoebel and Billy Meyers- which received its best remembered recording in 1926 by Doc Cook and his Dreamland Orchestra, a big band with Jimmie Noone, Freddie Keppard and Johnny St. Cyr on board). By such devices, Scaniazz keeps surprising you, avoiding predictable repetition of the overused ensemble-solos-ensemble format.

Their repertoire would surprise even dyed-in-the-wool experts, several titles rarely, if ever, having been recorded since the twenties. How many times, for example, have we heard Come On, Coot Do That Thing since its 1925 rendition for Paramount by its composer Coot Grant (pseudonym for Leola B. Pettigrew Wilson) and her husband “Kid” Wesley Wilson? Or Just Wait Till You See My Baby Do The Charleston by Rosseau Simmons, Clarence Todd and Clarence Williams, laid down in October, 1925 for Okeh by Clarence Williams’ Blue Five?

Two others, Lina Blues and Little Willie Blues, were composed and recorded in early 1929 by trumpeter Jabbo Smith, Brunswick’s answer to Louis Armstrong. Though Smith’s pyrotechnics highlighted the originals, the Scaniazz rides, by a five-man-sub-unit, place into clear focus the agitated, singing reed work of Jan Nilsson.

The remaining four range from the forgotten Sugar Babe (1925), words by Walter Melrose, music by Boyd Senter, to Copenhagen (1924) words also by Melrose, music by Charlie Davis, a foot-stomper that, despite its intricate routine, has been a favorite of older-style jazzmen since the great Bix Beiderbecke put it into the can for Gennett in 1924 with the Wolverine Orchestra. In between are (1) Jelly Roll Morton’s Buffalo Blues (1928), perhaps better known as Mister Joe (Morton frequently changed titles on his works), which dates from a 1928 session by cornetist Johnny Dunn, who went from king of the New York scene to instant obscurity as soon as Louis Armstrong arrived in town, and (2) It’s Right Here For You (If You Don’t Get It – ’Tain’t No Fault O’ Mine) (1925) by Perry Bradford, which still gets an occasional dust-off from Chicago-style cats.

So here’s all this esoterica from the Black jazz underworld, maintained not by the blood descendants, but by a white group, located halfway around the globe, who’ve picked up the universal message, poured it into the Copenhagen microphones, and sent it back here for us to rediscover. Truth sure is stranger than fiction sometimes. Anyway, in this case, it swings more.

NOTES by Tex Wyndham. January 1983

Tex Wyndham is a recognized authority on early jazz, having performed it at national festivals and on LP, and reviewed it for Mississippi Rag, The Second Line and other publications.

Year: 1982 | Title: Some Like It Hot | Ref: Stomp Off SOS1056